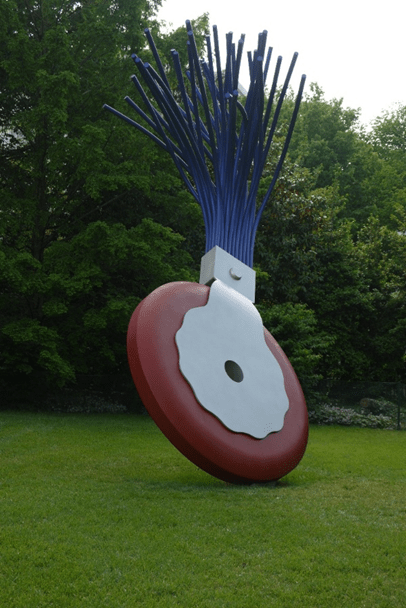

Typewriter Eraser, by Claus Oldenberg and Coosje vam Brigem

Washington, D C.. National Sculpture Garden

Preface:

I am adopting a new format. Each post will have a short version, a deeper read, and a section of supporting information.

Hopefully this will aid readers when short on time.

Short version:

A report by Policy Horizons Canada Disruptions on the Horizon, predicts that Canadians’ inability to tell truth from false information is the problem likeliest to occur in the next 3-5 years. This blog post examines several ways to understand the causes of the problem, and its dimension. Finding and accepting what is true is not primarily an intellectual, or information, process. It is a relational one involving what your social group thinks, often without regard to any reasons. I report on some strategies. I recommend three: support journalism’s attention to verifying information; support public and higher education by encouraging improved government funding of colleges and universities; and they, and the rest of us, following The Resonance Theory, must speak first to peoples’ existing values and emotions; present facts later.

“..if all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth” truth would invariably win out (John Milton, Aeropagatica, cited in Superbloom, by Nicholas Carr). “Let her and falsehood grapple; whoever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter?”

“…the error of opinion may be tolerated” as long as “reason is free to combat it.” Thomas Jefferson, 1801 inauguration address, also cited in Superbloom.

Deeper read:

The report:

An April 2024 report by Policy Horizons Canada Disruptions on the Horizon, predicts that Canadians’ inability to tell truth from false information is the problem likeliest to occur in the next 3-5 years. Its impact will be lower only than the loss of biodiversity, and ecosystems collapse; civil war in the U.S.; and a world war. The inability could involve not understanding true and false; not knowing how we engage each other; the occurrence of synthetic information and deliberate deception; the dangers of rhetoric;1 and the significance, place, and trustworthiness of education and journalism.

The report says

Individuals could choose to focus on their own survival, potentially undermining democracy and the social contract. If more people lose trust in decision makers such as governments and central banks to restore the widespread ability to meet basic needs, they could become more vulnerable to extreme, populist, and anti-establishment leaders and groups. Alternatively, they may look for collective solutions, such as labour organization and other social movements.

The agency defines itself this way:

Policy Horizons Canada is the Government of Canada’s centre of excellence in foresight. Our mandate is to empower the Government of Canada with a future-oriented mindset and outlook to strengthen decision making. The content of this document does not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Canada, or participating departments and agencies.

How this problem comes about:

Political deceit:

It is generally accepted that there have long been efforts to deceive us, even before social media. Recent politics exacerbate this: who believes a politician other than one you know well2? You may remember the latest American vice-presidential debate, during which Vance recounted the story of the immigrants eating small dogs. The moderator citied contrary information, and Vance complained that he had expected no fact-checking. I infer that he knew the statement was false and resented the moderator’s pointing that out: Vance believed that lying wasn’t wrong, but identifying it was. What to do with a person who knows he’s lying and persists?

Government and political deceit:

The current U.S. government is altogether unbelievable, whether it is the president’s statements or social media messages, tariff declarations, or musing about the future; or the government’s drug, food, environment, financial, or defense, administrations. There are many reasons why it is difficult to discern what is true there. The principal one is that so many powers in our society do not bother to know or assert truth, e.g., Here’s how many false claims Doug Ford made in just one week.

There can be a sort of in-between effort, not to deceive, but not to be clear either. Politicians generally, if not playing to their base, must try to answer constituents’ and party members’ questions without needlessly opposing the questioner. Some have the ability to answer in a way that might be construed as supportive of one point of view, (e.g. “I hear you,” “that’s certainly one point of view,” and “an excellent question….”) without actually saying so.

Removing the difficulty of knowing truth ought to be simple, but is not.

Corporate deceit:

There is colossal intentional deception by the companies who provide the technology for social media (see Careless People: A Cautionary Tale of Power, Greed, and Lost Idealism, by Sarah Wynn-Williams; The Square and the Tower: Networks and Power, From the Freemasons to Facebook, Niall Ferguson; An Ugly Truth: Inside Facebook’s Battle for Domination, by Sheera Frenkel and Cecillia Kang). The sheer audacity, deliberateness, and pervasiveness cannot be described here. Not only are the consumers being deceived, but so are many governments regarding Facebook’s activities in their countries. These describe their actions work thoroughly.

The social media are deceitful by their very nature:

Jonathan Haidt3 social psychologist and Professor of Ethical Leadership at the New York University Stern School of Business, asserts that the Z generation and younger people have been deliberately neurologically conditioned by smart phone technology to exhibit certain repetitive, reward-seeking behaviours, and thereby forfeit more self-assertive, independent, thoughtful behaviour. He calls this The Great Rewiring: the transition from flip- and other basic phones, to smart phones, together with faster internet service and more apps that perform tasks for you, and help organize you, It created many new pathways for Gen Z, and atrophied others. He quotes a Facebook and Instagram developer, who wrote that the goal was to create a “social-validation feedback loop…exactly the kind of thing that a hacker like myself would come up with because you’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.” The developers of these media and phones seek to manipulate their users. Gen Z is trained – not by the previously normal in-person, peer experiences within which to discern their place, level of prestige, likability, and success at getting along pleasantly; but by adult manipulation of their remote experiences, which cast them into adult values (or absence of values), and ways of expressing things genuinely or falsely. For these, the young people have no natural defenses. Gen Z was the first to go through the confusion of puberty in the age of the smart phone. https://www.thestar.com/news/world/united-states/teens-say-they-are-turning-to-ai-for-advice-friendship-and-to-get-out-of/article_5eec1df9-faa4-5f7f-ba55-3084da29a8fe.html

There is other evidence that the phone-based life may diminish our ability to thrive as mature adults, for example a recent article in the “Financial Times” https://www.ft.com/content/43e2b4f6-5ab7-4c47-b9fd-d611c36dad74https://www.ft.com/content/43e2b4f6-5ab7-4c47-b9fd-d611c36dad74 about the decline of coupledom, i.e., not just decline in marriages, but decline in getting together in person, which the authors ascribe partially to the rise of on-line living.

The slippery nature of Truth:

Knowing what is true has long been difficult. Robin Reames (The Ancient Art of Thinking for Yourself: the Power of Rhetoric in Polarized Times) writes that in Plato’s time the written word was not yet common. Argument, reasoning in public debate or during instruction or conversation, were conducted orally. The force of a presentation through clever rhetoric and persuasion, emotionally evocative words especially in metaphor, and emotional presentation, won over the audience. Counter-arguments were cast in the same molds. Truth was found in the winning argument. There was not the opportunity to examine the facts, the line of thought and the meaning of the words after a speech, because it was not written. It was not facts, but strength of oral presentation, which established truth. Reames says that as writing became more common it was possible for some to consider the argument more carefully, especially the facts.

Knowing what was true then, was a matter of either having one’s own possession of facts and/or being persuaded. I would suggest that being persuaded by something in writing is a surer source of knowledge than hearing an oration. If the orator has an established reputation for truth and honesty as demonstrated by the texts of speeches and by deeds, then one can sit back and enjoy the entertainment of good oratory and rhetoric (very rare, indeed). Nonetheless, the dangers of effective rhetoric are real, as illustrated by her book and others.4

Simon Winchester (Knowing What We Know: the Transmission of Knowledge from Ancient Wisdom to Modern Magic offers more history going back to Plato’s Theatetus, which argues that there is Justified True Belief. Winchester summarizes Plato’s argument: you see an animal which you declare is a camel, believing this to be true. Knowing that there will be skeptics, you seek outside information to confirm this for yourself and them: You cite the humps and general physical description, Google up a photo labelled “camel,” and cite public knowledge that camels are known to live in the area. Thus you justify your belief: you assert that you are right that this is a camel. Winchester knows that there have been arguments against this form of reasoning since Plato’s time, and provides some of that history. His is a good description of a respectable argument that something is a true fact.

But with the rapid and vast information cascades we have now, according to research cited by Carr (see below, also Cass Sunstein Republic.com), lies get more attention than truth because of their novelty, and repeated information gains acceptance as truth, an acceptance reinforced by the group.

Possible means of solving the problem:

Education and its limits:

One would hope that normal education in schools and in higher education, would equip and encourage people to seek accuracy and pursue informed consent. But scarcely a day goes by without a news story about either university students or teachers using AI. The presence of AI may no longer be reliably detected https://www.thestar.com/business/canadian-researchers-create-tool-to-remove-anti-deepfake-watermarks-from-ai-content/article_3dbbc1b7-63af-596c-a732-116a33786524.html At what point do people think for themselves, and how do we know they are not parroting a machine, or being one?

There is also the uncertainty of having enough education to build confidence in your knowledge. I led a team to conduct ethics training for an “alliance” of companies trying to restart an old nuclear generating station. We trained them to use a particular ethics decision-making template. We used the same ethics decision-making template to conduct public discussion, to help the public answer this question:

“How do we know

that we know enough,

to be able to discern

whether the company are working with our good interests in mind as well as the company’s?”

That question about being sufficiently educated and perceptive to understand this world, is central to the worry about people being unable to tell the difference between truth and other things. We should encourage governments to better fund public schools and high schools, and colleges and universities, with attention to both STEM and the arts. The arts must help people empathize with others in person (see the above on the nature of social media), and learn to look outside the limits of particular disciplines. STEM is necessary to cope with an increasingly technical world. The importance of this juncture of the two can be seen, as an example, in Wynn-Williams’ book. There is an account of her discussion with Facebook’s COO Sheryl Sandberg: the topic was using Facebook to promote contributions of body organs. As the author tried to explain the different cultural and religious perceptions and values in some places, Sandberg demanded: “’Do you mean to tell me that if my 4-year-old was dying and the only thing that would save her was a new kidney, I couldn’t just fly to Mexico, get one, and put it in my handbag?’” (This illustrates the ability to discern how tech can improve human life, expect empathy for one’s own, but not extend empathy to whoever gave the kidney.)

Journalism and its limits:

We’re all familiar with the dangers of public misinformation and disinformation. Many of us have been proofed against trusting “legacy media” for impartiality and accuracy.

The journalism profession takes steps to validate their information. For example, the Canadian Print Journalism Professional Code of Conduct emphasizes ethical journalism principles:

Key Principles of the Code of Conduct

- Accountability: Journalist4s are responsible for their work and must be transparent about their sources and methods. They should provide opportunities for affected individuals to respond to their reporting and address any public concerns regarding fairness.

- Transparency: Journalists should be open about their sources and any potential conflicts of interest. This includes clearly distinguishing news content from advertising and sponsorship.

- Accuracy: Journalists are committed to verifying facts and ensuring that the information presented is correct. They must promptly correct any errors that may arise in their reporting.

- Independence: Journalists should operate free from undue influence or bias, allowing them to report objectively. They must resist any attempts at censorship or interference that could compromise their editorial independence.

- Fairness: The code requires journalists to represent diverse perspectives and avoid personal biases in their reporting. They should strive for balanced coverage and ensure that all relevant voices are heard.

There are other associations which assert similar values. (I’m not sure why these are not built into the same code for everyone, but it is certain that many journalists have given careful thought to the issues, and that they truly intend to report accurately.)

Even so, the Globe and Mail standards editor Sandra Martin https://www.theglobeandmail.com/standards-editor/article-when-facts-are-fuzzy-whore-you-going-to-call-joe-rogan/ reports that news consumers increasingly get their news from Chat GBT. I doubt that this will add to the public’s sense of reliable news, and it suggests that some people don’t care.

Another concern lies in “vertical videos,”, i.e., videos of reporters speaking their information (meant to be seen vertically as one scrolls through, without having to rotate the phone to see a landscape view). The idea (see Martin’s links) is to appeal more to the reader and provide news in the way people are likelier to receive it. But videos without transcripts run the danger that spoken words can sometimes persuade that truth is found in them alone, even though one cannot easily check what was actually said and analyze it.

Still another issue is “fake news,” i.e., deliberate fakes of legacy news service products. See https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/video/9.6837591 to understand how this is identified.

These possible solutions will encounter group loyalty:

People can become strongly defensive about their current views, often out of loyalty to a specific group, or fear of them.

As Agnes Callard writes (Open Socrates: The Case for a Philosophical Life):

We navigate our lives by way of answers as to what things matter or have meaning. …Most of the answers that anchor our agency in the world concern our relationships to the people we are close to.…My reputation is not something I can ever have in my own possession: it is located outside me – outside my body—in the minds of other people in the community.

Loyalty may be difficult to compromise, because people group themselves ever more by values resulting from the interaction of genetic tendencies and culture influence: “Before long, that wall [between nature and nurture] will be completely decimated as social position influences genetic stock (of the next generation), which in turn will affect social position” (The Social Genome: the New Science of Nature and Nurture, Dalton Conley).

Resonance theory: the threat but also the solution?

I focus, now, on one particular explanation of how electronic disinformation works: Nicholas Carr (Superbloom: How Technologie of Communication Tear Us Apart), cites another author in explaining how Facebook’s Newsfeed works:

In an age of mass media…people have more information than they can handle. To seize their attention and influence their thoughts and behaviour, you don’t need to give them more small stuff to think about….You need to activate the information and attendant emotions already present in their memory.’ In communicating at electronic speed, we no longer direct information into an audience, but try to evoke stored information out of them, in a patterned way.’ A successful message doesn’t deliver meaning; it calls forth meaning.

This is called The Resonance Theory of Tony Schultz (The Responsive Chord).

Perhaps this is where we should begin: we want to counter lies which are built on what people feel4. Of course, it is difficult to know that. There is no reason we should presume that a person is thinking only one thing, or has only one set of feelings about any topic – there may be an assortment at any given time. (We will not use Facebook’s information about people, because that is just unethical. It is far too powerful and doesn’t seek informed consent.) It is a matter of crafting our true information and story based on an attractive metaphor, to appeal to certain emotions other than fear and anger (always two sides of the same coin). I offer below an example of a story which I think can become true if we take the right measures. It is based on facts known now, and upon the metaphor “a place.”5 Our feelings are often expressed orally or in writing as metaphor or analogy: “I feel as if…” or “I feel like…” or “I am the mouse in a cat-and-mouse game.” Aside from rote memory, we learn things primarily as metaphors and allegories, or similes.

I suppose this might seem to be manipulation — not as clean as simply laying facts on a table, inviting people to examine them (if they have the time and interest), and hoping they will pick up on the right facts and make the rights decisions. That is the formal education model.

Rather, it is reading the audience and offering what you know and believe to be true, expressed in a way that will call out emotions you hope they have inside them. There is no reason we should not do it to offer truth. Every rhetor does this – tries to feel out the audience for what might appeal. We are trying to persuade by honesty and truth, rather than manipulate by lies and invoke fear and anger. Facts can be part of the message, but we must first evoke the feelings from within the person. These can be powerful metaphors: child, grandchild, grandparent, baby, bothers, sisters, parent, home, favourite vacation spot, garden, gardening, tapestry, weaving, woof and warp, famous vacation spot, personal favourite refuge (place or state of being), anniversaries of meeting, engagement, death, birth, wedding, divorce. spectacular event (e.g., Woodstock), cancer or other diseases, well-known movie, piece of music, theatre production (an easy allusion to a particular generation but perhaps not another), Christmas and other special days which denote both religion and secular celebration, things military (battles, wars, double-edged sword, sword-into-plowshares), memorable school events, hero or much-admired person of the present or past, “pie in the sky,” pipe dream, road, way, the way, path, winding road, straight road, river, creek, tall or old trees, sky, rain, snow, dawn, sunset, twilight, breeze, storm, wind, night, midnight, passageway, ship, or boat.

The rhetor or story-teller must know the specific qualities of the audience, e.g., residents of the hometown, specific ethnic population, particular generation(s), etc.; and carefully choose allusions, vocabulary, education level, common expressions among gender groups or ethnic groups, lines of work, place of origin, current residence or employment/career, or socio-economic circumstances such as married, single, widow/widower, and alone. Know to whom you are listening and talking.

This is a hit or miss method, and you may think it is enormous effort without a likely payoff. But because of the strong need to belong to groups, we may be able to evoke commonly held emotions from whole groups: if we have evoked the appropriate emotion in one person or group, then perhaps in many or all as well. If we can satisfy one’s criteria for truth, we may possibly satisfy the criteria of many others as well.

The facts and truth that we help people accept, must hold. They must be reliable over time. They must abide and be the First Principles, i.e., the bedrock on which people can stand as they seek out what else may be true. People must be able, in times of doubt or stress, to return to the First Principles, and still find them true. Those First Principles must continue to show them the way forward e,.g., the world is warming quickly. Therefore, methods to avoid the consequences, and adapt to those which cannot be avoided quickly, must be found.

For example, in the story I have offered below, I hoped to evoke the feeling that everyone wants to have a place in life where they matter to themselves and others as well; where they matter, not because they are useful to others, but because they are valued in and of themselves. (I acknowledge that not everyone wants to feel they have a place; some are rugged individualists, or loners.) But to those who do, we an offer some truth about how to get there based on facts as we know them. This is quite different from laying facts on a table, and demanding that people look at them all, assemble them into the same truth that we have, and act.

Finding and accepting what is true is not primarily an intellectual, or information, process. It is a relational one. We build relationships by doing something together that builds what we both want, and by sharing our stories in which we both can stand at the same time, for a while. What is it like to have a place?

Conclusion:

Because journalists work hard to vet their information, we must support news efforts by subscribing to them, commenting on their work, and writing letters to the editors. Because formal education is so central to understanding the world, we must support it also.

But, equally important, those who write and speak news and essays , and those who teach, must also draw out peoples’ emotions, and speak to those with metaphor, story, and then facts, to enable people to discern what is true. So must the rest of us: anyone of us who is involved in groups of any type; any one of us who can chat with strangers at a social event. Find people to listen to. Hear what is important to them; listen for their life metaphors. Then speak to those with empathy, while providing information which you regard as true. Listen to the response, and watch the body language. Learn from these, and persevere with these and others.

1 What do we know, and how? – Upon reconsidering…

2 Reconsidering Again, part 3: Character in Decision-Makers – Upon reconsidering…

3 Jonathan Haidt The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. See also Reconsidering again, part 1 – Upon reconsidering…

4 The Knowledge lIlusion: Why We Never Think Alone, Steven A. Sloman; The Influential Mind: What the Brain Reveals About Our Power to Change Others, Tari Sharot; Strange Contagion: Inside the Surprising Science of Infectious Behaviors and Viral Emotions and What They Tell Us About Ourselves, Lee Daniel Kravetz; How Emotions Are Made: the Secret Life of the Brain, Lisa Feldman Barrett; Connected: the Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives, Nicholas A. Christakis; The Secret Life of the Mind: How Your Brain Thinks, Feels, and Decides, Mariano Sigman; The Ideas Industry, Daniel W. Drezner). See Informed Consent in Our Lives – Upon reconsidering…

5Enough Said: What’s Gone Wrong with the Language of Politics, Mark Thompson; The Ancient Art of Thinking for Yourself: the Power of Rhetoric in Polarized Times, Robin Reames; and At a Loss for Words: Conversation in an Age of Rage, Carol Off. See also What do we know, and how? – Upon reconsidering…

5 A Place

Everyone wants a place in life. You know what a place is? It’s when you get up in the morning and greet your family, or your friends in person or remotely, it matters to them that you are there. They would care if you were not.

A place has several contexts – you feel you can rely on the public systems to work well so they don’t require much attention from you. You feel accepted in your social context –no one es you for your differences, you don’t judge them either. You feel safe, secure, delighted to accept the new day.

That’s a place.

Now, after decades of climate disasters, you have come through, working right through them to get beyond just recovering for a while, and then rebuilding in the same old way.

You flourish. We flourish.

We became quite precise at predicting dangerous weather – all of it: drought, floods, winds/hurricanes/derechos, blizzards, intense heat—and built for it. We designed whole communities* that could withstand the hurricanes across the infrastructure: no one will be washed away, nor our houses nor businesses, nor streets, nor fields, nor pastures. We learned to build so that heat could be resisted with minimal energy use. We recovered from the traumas of the disasters, and built new, so we would not suffer again as the earth, seas, and skies punished us. We learned how to farm and pasture without destroying again.

We are very good at saving forests from fires, even the years-long underground fires, and became very good at managing the reusable resource of wood.

We found all the deep underground, ancient channels that naturally carry water long distances underground** and now use them to move water from areas of abundance to areas of drought. We learned to let the seas do what they want in their natural realms, and we stopped trying to change them and their life-forms. We built soft, natural surfaces to replace hard surfaces as much as possible, to receive the waters without flooding. We welcomed back the beavers and the natural salt marshes and wetlands, no longer building our abodes too close to water and flood zones.

We learned to live and work at night sometimes, when daytimes are too hot.

We use sustainable electricity while we continue to reduce the carbon we produced before the disasters. Only enough for our needs – we abandoned the consumer economy with its devouring appetite for growth. Our “economy” is designed to help everyone flourish, including the disabled, confused, and incapable. There are no “misfits.” Everyone fits in. It’s not just for the high-achievers and competitors.

We learned that wars are what governments and factions do when they can’t solve their own problems. Now we have too few young people to fight, and we learned not to fight with remote weapons and computers either. If someone wanted to host a war now, no one would attend.

We expect to have more children, but not as fodder for war and cheap labour. As we age, we will need their help, but we will not have it by dominating them or demanding it. We will ask, and we will hope to deserve it so that it is freely given.

We learned how to lead without dominating, and taught our government officials and politicians how to do that. Government now exists only to help everyone flourish, and to foster beauty. Governments learned to fund this better economy, to fund all costs of adaptation, recovery, and survival in the early days of disasters.

We strictly watch how we use the rest of the world. We flourish, but not at the cost of anyone or anything else in this world. We live in mutual regard so that all flourish.

And we have a place.

* Florida neighborhood stays strong after hurricane hits disaster-proof homes: ‘We have to adapt’

** Paleorivers are deep underground channels carved long ago by glaciers. They and hyporheic zones (beds under the bottoms of rivers which can receive overflow, filter it, and let it run down their lengths to other places and bubble up some distance away), can move waters from flood areas downstream to dryer locations. See Water Always Wins: Thriving in an Age of Drought and Deluge, by Erica Gies.

Open save panel

- Post

about:blank

Glenn, et al,

I find myself deeply concerned regarding the potential and evidential usage of AI as a tool for misuse of both âfactualâ information or believable information. Both of my 20âs sons are adamant they do not trust AI and the infractions such mischief is creating amongst their group discussions they are experiencing is yes, on the one hand generating lively âdiscussionsâ, yet, in the final analysis it has sown discord and to some degree distrust. Likewise, I am amazed at what I sometimes hear coming out of the mouths of supposedly educated professionals. That the south of the border executive and legislative administrations are twisting facts like kites in a strong wind, attempts to follow mainstream media has, for myself, become so unreliable that I no longer believe what I am seeing or hearing. I have gone to independent journalism and recommended literature reading, while they remain in existence to verify or source information. As Noam Chomsky cites in his book Hegemony and Americaâs Quest for Global Domination one of the foundational aspects of true authoritarianism is control of the media. This also includes what is said verbally to the public.

What astounds me is what about the next generations, the ones to come, when we have secured firmly that lying is common practice and indeed accepted as fact. How do they discern the truth when we who still have some capabilities in existence, disappear?

I am becoming fatigued with little heart for it anymore.

Ray

RAYMOND CHANDLER

PARTNER & COO

MIDDLE KINGDOM ENTERTAINMENT CORPORATION

cell- 905.706.5221

http://www.middlekingdomentertainment.comhttp://www.middlekingdomentertainment.com/

ray.rcp@outlook.comray.rcp@outlook.com

[cid:image001.jpg@01DC007C.A7135900]

Thanks, Glenn, for your latest, thoughtful article. I like your new format. I think, in effect, it presents your posts on the model of research papers–with an Abstract; Body; Conclusions; and References. As a retired academic, I feel right at home 🙂 Keep up your good work Bill